Metro areas like Orlando, Florida have seen the number of homes for sale jump 50 percent so far this year, but Greater Boston’s only seen a 17.4 percent rise. iStock photo

Much of the United States is starting to see its years-long drought of housing inventory let up, but Massachusetts is still lagging behind.

Due to the high interest-rate environment dating back to 2022, homeowners have held on to homes they might have otherwise sold as the ultra-low rates on their current mortgages cannot be matched.

Sellers are then faced with not just high-interest rates but also higher home prices, which combine to either put the home they want out of reach or make it seem bad value for money.

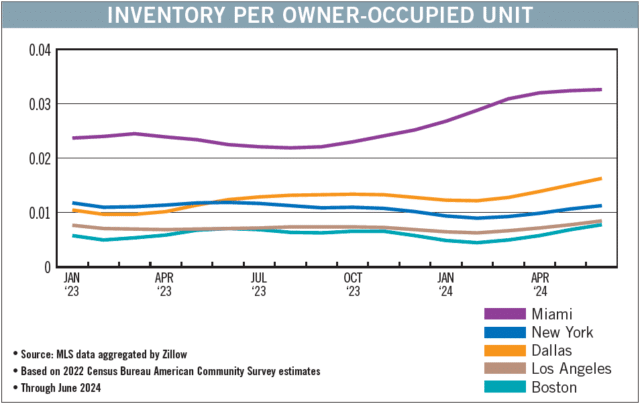

The total number of homes on the market nationwide has risen throughout 2024, slightly increasing by 4 percent from May to June and currently stands nearly 23 percent above last year’s low level according to multiple listings service data compiled by Zillow that includes single-family homes and condominiums.

While states such as Florida have seen massive growth in inventory so far this year, the same can’t be said for Massachusetts. According to Zillow, while Orlando and Tampa all saw year-over-year inventory growth over 50 percent, Greater Boston saw a jump of just 17.4 percent from some of the lowest inventory levels ever recorded.

The same boom can be seen in houses for sale with Florida boasting 198,465 homes for sale (40.1 percent increase year over year) compared to Massachusetts’ measly gains of 18,144 homes for sale (12.9 percent year over year) according to data compiled by Redfin.

Graphic by Bill Samatis | Special to Banker & Tradesman

Low Supply, Less Volatility

Gibson Sotheby’s International Realty CEO Coleen Barry added that Massachusetts – Eastern Massachusetts in particular – has calmer cycles compared to other parts of the United States.

“We don’t have as much of – and forgive the expression – but a boom-and-bust cycle here, as you tend to see in other parts of the country,” she said.

In markets like Miami-Dade area or Las Vegas, there are more peaks and valleys compared to Eastern Massachusetts where housing market shifts aren’t as dramatic.

“The good news is that when the market goes down, it’s what we would call a short and shallow shift, right? So, it might go down by 5 percent or 10 percent or something like that typically, but it doesn’t last for – typically – longer than 18 months,” she said, comparing that to “other markets where you might see reductions in pricing that could be in the range of 30, 40, 50 percent – something really wild like that and it might last for a couple of years or three years.”

Gerry Bourgeois, senior advisor to the CEO and COO at Lamacchia Realty, said that while the interest-rate environment plays a factor when comparing states like Florida and Massachusetts, a more important element is the amount of new construction. While Florida has plenty of space to build, the same can’t be said for the commonwealth, particularly Greater Boston.

“Comparatively speaking, yes, there’s new construction in Massachusetts and in New England, but not barely at the other volume of new construction that we see in the Sun Belt, in places like Florida, places like Texas, Arizona, where they had a lot of not just building, but in some cases over building,” Bourgeois said in an interview. “So, the fact that it’s rather expensive to build a home in Massachusetts, for instance, is one of the things that has kept the prices high because we didn’t have that overbuilding.”

Are Interest Rates the X-Factor?

High interest rates are a common denominator in explanations for Greater Boston’s lack of inventory. But cutting them won’t necessarily create a more balanced market or boost inventory, experts say.

“My fear is that, no, it’s not the case, and it might actually drive prices up,” Barry said. “If the cost of borrowing money is less, then people are more likely to borrow more of it.”

And lower interest rates cannot fix the problem of a lack of land and other challenges to building new inventory.

In suburban markets such as Wellesley, Needham or Natick, local government opposition to new development and high construction costs work together to keep the price of newly built units high.

Sam Minton

“It makes it much harder to build units or homes in the segment of the market where we really need them and you can build a home and put a $3 million price tag on it,” Barry said. But “there’s a limited number of buyers in that pool. The pool that’s greater and needs more inventory, is in a price point where it’s very difficult to get to that.”

While lower interest rates might encourage some owners to list, and might make it easier for developers to finance new homes, Bourgeois said, it also might drive prices higher.

“If rates come down considerably, let’s say to the low fives, for instance there’s a lot of pent up demand on the sidelines, which means that there’s going to be a lot of buyers that not only can now afford property that they couldn’t before or want to afford, and then the ones that could can afford more now,” he said. “It’s a double-edged sword.”

But there are some opportunities for prospective homebuyers to take advantage of.

Barry said that buyers might take advantage of the anticipated rate cuts by selecting mortgages that allow for a one-time rate reduction. Lenders offering these types of products typically let borrowers reduce their loan’s rate if the typical market interest rate comes down within a year. In other cases, buyers could refinance.