From prosperous manufacturing hub, to decaying backwater, to blossoming knowledge-and-tech capital, Greater Boston has known many fates.

Welcome to Boston, the city that reinvents itself every century or so.

That’s one takeaway from a magnificent and masterful book on the history of Boston written by Dan Dain, a top commercial real estate lawyer by day, author at night.

Dain’s book, still in draft form but in search of a publisher, looks at all nearly 400 years of the city’s history with a particular focus on the ebbs and flows of its economic fortunes.

Yet the manuscript is much more than that, covering everything from the original topography of the peninsula that would one day become Boston to the city’s role as the birthplace of both the abolition and anti-immigrant movements.

And the book also offers both an implicit and at times overtly stated warning, that Boston’s current success is not cast in stone, and that the progress of recent decades came only after 60 to 70 years of stagnation and malaise covering a good chunk of the 20th century.

“Boston is ascendant. But it has not always been so. Indeed, for most of the twentieth century, Boston was at a nadir,” writes Dain, chairman, president and co-founder of Dain, Torpy, Le Ray, Wiest & Garner, PC. “Trying to understand what has caused Boston, throughout its history, to swing between periods of urban success and failure is what has motivated me to explore the history of Boston.”

The Cycles of Boston History

Boston’s first and wildly successful transformation began in the early decades of the 19th century, when the port was in decline and the region’s farmers were facing new competition from more fertile soil in western lands.

Dan Dain

The Industrial Revolution helped transform Boston – and what would become a ring of mill cites in its hinterlands, like Lawrence and Lowell – into a major hub of production and commerce.

Along with a thriving economy, the city’s intellectual and cultural life boomed, with the birth of the Abolition Movement just one of many things reenergized the city’s reputation as the nation’s intellectual capital.

Boston also grew both in land mass and population. Fill hauled in by the trainload to create the Back Bay and parts of South Boston, while immigration and annexation of its suburbs more than tripled its population – from 177,840 in 1860 to 560,892 by 1900.

But after a century on top, the 1920s ushered in a long period of decay and decline.

The larger economic, political and social forces that drive history can be fickle, and textile and other manufacturers began to depart for the South in search of cheaper labor.

The shift ushered in decades of stagnation and decline, reinforced by an intensification of tribalism and corruption in politics, personified by Mayor James Michael Curley, who famously served part of his final term in office while serving time in federal prison.

With the city’s piers rotting and new development and investment a thing of the distant past, by the 1950s a new generation of Boston business and political leaders were desperate to shake things up.

We all know what happened next, with the West End, a poor but vibrant neighborhood at the time, bulldozed to make way for the Charles River Park luxury apartments, and Scollay Square flattened to make room for a new City Hall and a host of other Brutalist style government buildings.

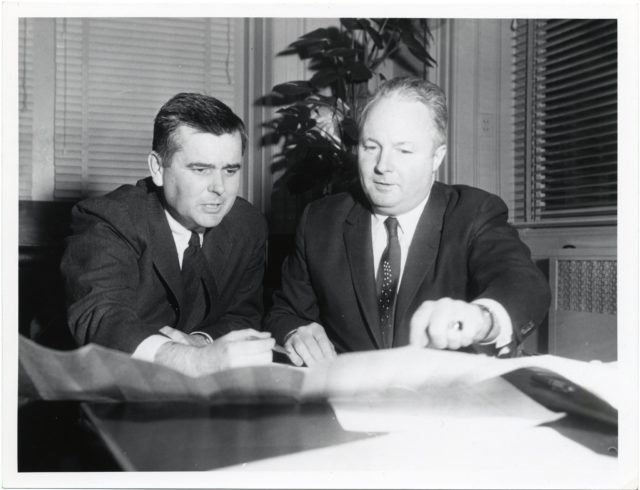

In popular memory, Boston Redevelopment Authority Director Ed Logue, left, speaking with then-Mayor John Collins, is credited with kick-starting Boston’s revitalization. Dan Dain disputes this, saying Logue and the era’s developers tried to suburbanize the city. City of Boston photo

A City Reborn Again

It’s common to trace Boston’s comeback to the 1960s and ’70s, however tragically flawed those grandiose attempts at city rebuilding may have been.

Interestingly, though, Dain sees these years as an attempt to impose a flawed vision of suburban-style development on Boston’s urban core.

The leveling of the West End was accompanied by a surge in highway building designed to funnel commuters from suburb to city to back again.

Timeline: Real Estate and Banking’s March Through Mass. History

Rather, Dain traces the start of Boston’s second great transformation to the early 1990s.

With its renowned universities and hospitals, Boston was to reap the benefits as New Economy industries like high-tech and life sciences rose from the ashes of the 1980s’ Massachusetts Miracle.

The city’s longest serving mayor, the late Thomas M. Menino, provided stable political leadership during this critical period, with his attention to pothole-filling and the other nitty gritty of city management earning him the reputation as an “urban mechanic.”

However, Dain singles out former Mayor Marty Walsh for particular praise, with Walsh building upon Menino’s legacy to foster an epic development boom that included thousands of badly-needed new housing units.

Boston issued building permits for roughly 4,000 new units a year during Walsh’s tenure. By contrast, the city added just 1,072 new homes, apartments and condominiums during all of the 1990s, even as it gained 15,000 new residents.

“Marty Walsh, has a more legitimate claim to credit for the dramatic acceleration of high urbanism,” Dain writes.

Scott Van Voorhis

A New Crossroads Approaches

Dain’s draft was completed before Mayor Michelle Wu, whose development policies are still a work in progress, had gotten her feet fully on the ground.

But 30 to 40 years into an urban renaissance that has propelled Boston into the front ranks of global cities, it’s fair to ask, though, whether we may be approaching a new crossroads.

Interest in Boston – and by extension its suburbs – show no signs of abating among key growth industries, with developers pushing plans for tens of millions of new lab and research space across the metro area.

That said, such growth is increasingly running into structural obstacles in the form of astronomical housing costs – themselves the legacy of decades of underbuilding – traffic-choked highways and a public transit system in full meltdown mode.

And without an effective remedy to our increasingly dire housing and transportation crises, it’s hard to see how this current boom can continue indefinitely.

As Dain’s book amply shows, progress is not a given and stagnation, if allowed to set in and become the default, can prove deadly.

Scott Van Voorhis is Banker & Tradesman’s columnist; opinions expressed are his own. He may be reached at sbvanvoorhis@hotmail.com.