A waterfront building is reflected in the waters of Boston Harbor. Developers who lease properties in the city’s Raymond L. Flynn Marine Park will be required to help pay for harbor flood defenses.

Developers in South Boston’s Raymond L. Flynn Marine Park will chip in toward projects designed to stave off sea level rise under a new resiliency funding formula.

Four developers have agreed to make annual payments toward a sea wall project – estimated to cost up to $124 million – to prevent a majority of the 191-acre park from expected flooding on a monthly basis in the latter half of the century.

“We saw that we had several large lease deals coming and had the opportunity to create a public-private partnership to fund the infrastructure for climate resiliency,” said Devin Quirk, director of real estate for the Boston Planning & Development Agency.

The BPDA devised the cost-sharing program as the city prepares a series of coastal defense projects in the Seaport District and other waterfront neighborhoods. Because all of the land in the marine park is publicly-owned, the agency is asking developers to agree to annual payments as new projects are proposed or leases are transferred to new ownership.

Build Now, Pay Later

Boston-based Marcus Partners agreed to pay up to $250,000 a year toward resiliency projects as it seeks approval for a 228,000-square-foot office-lab development, replacing the Au Bon Pain headquarters and bakery.

Other developers that have agreed to payments include Millennium Partners, which received approval in December for a 380,000-square-foot office-lab complex at 2 Harbor St., and Cronin Development, which is proposing a redevelopment of the Boston Ship Repair property at 24 Drydock Ave.

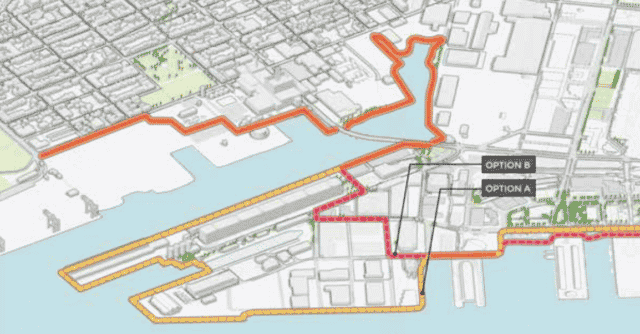

Boston hopes to build a million seawall to protect commercial property from climate change-caused floods. Two options are under consideration protecting different amounts of real estate. BPDA image | Courtesy

But developers won’t be writing any checks in the near term: payments will be assessed the year after an infrastructure project is completed, and developers won’t be required to begin payments until 50 percent of the park’s leaseholders have signed up. The city would borrow money for the project costs upfront.

Quirk said the policy addresses the “free rider” problem in which one developer pays for improvements that others benefit from later on. The developer’s share of the cost is determined by their project’s percentage of the marine park’s total building square-footage, which is currently 3.7 million square feet.

City agencies are evaluating two options for the marine park sea wall improvements, with costs ranging from $108 million to $124 million, according to Rich McGuinness, the BPDA’s deputy director of government planning. Developers’ payments as a percentage of the overall project costs are yet to be determined, because of uncertain funding levels from public sources.

A Model for Resiliency Funding?

Developers have made a recent series of big-ticket acquisitions in the eastern end of the Seaport as prime development sites dwindle closer to downtown Boston. The marine park’s current zoning sets aside 95 percent of the park for maritime and other industrial uses, but higher-rent-paying developments could be on the horizon.

The state Executive Office of Environmental Affairs is reviewing a master plan update that would allow more commercial uses on the upper floors of buildings, presenting opportunities for developers looking to tap into the life science boom. The Davis Cos. of Boston is proposing to build a 4-story, 330,600-square-foot addition atop the 88 Black Falcon complex, which it’s ground-leased since 2017.

Levi Reilly, director of development for Marcus Partners, described the fund as a “thoughtful approach” to long-term resiliency planning.

“We feel that comprehensive resiliency planning investments and investments made at the neighborhood level are critical,” Reilly said in an email. “All of this proactive work gives us assurance that our investments in the marine park and, more importantly, the users of our buildings will be protected from future flood events so they can focus on the work that drives our economy.”

Steve Adams

The marine park improvements are a small portion of what’s expected to be a multi-billion-dollar price tag for shore defenses in Charlestown, East Boston, downtown Boston, Dorchester, North End and South End reflecting a projected 40-inch rise in sea levels by 2070.

Some of those neighborhoods, such as East Boston, will require significantly more public investment, because they’re dominated by small residential properties, said Alice Brown, chief of planning and policy at Boston Harbor Now.

“If there’s a vulnerable community that’s made up of a lot of low-income people, it’s going to be fully on the public sector to protect those residents,” Brown said. “It becomes more complicated.”