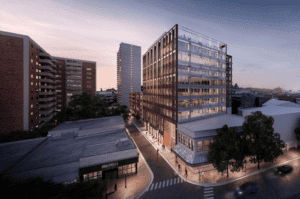

The city of Malden created an office of strategic planning and community development in 2021 after a surge of multifamily and life science development in recent years. Pictured is Quaker Lane Capital’s 188,000-square-foot 11 Dartmouth office-lab project, approved last year. Image courtesy of Gensler

Multifamily housing and large-scale commercial projects frequently generate controversy and opposition in Boston suburbs, but real estate developers say many of the biggest impediments start with understaffed and fragmented town hall bureaucracies.

Nonprofit community development corporations and smaller private developers alike say they face steeper hurdles getting projects completed in communities with small staffs, or avoid doing business in them entirely.

“CDCs certainly depend upon effective, well-run municipal government to get their projects done,” said Joe Kriesberg, president of the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations. “You can engage with full-time professional planning staff so the process runs more smoothly and more predictably. And if the answer is ‘no,’ you can know that sooner in the process.”

In Hudson, legwork by professional planning staff has been critical to progress on a housing conversion of a former police station, said Caitlin Madden, executive director of Newton-based Metro West Collaborative.

Following a request for proposals, Hudson officials selected Metro West Collaborative to redevelop a former police station as 40 affordable units. The project quickly acquired its zoning approvals and is now seeking affordable housing tax credits from state officials.

“The town did a lot of groundwork to generate support for affordable housing at that specific site. The town planning staff really helped shepherd the project through and made sure we were talking to the right people,” Madden said.

For Housing, Time Means Money

The nonprofit CDC has a territory of 24 MetroWest-area suburbs and is currently pursuing affordable housing projects in Hudson, Medway and Newton. In Newton, it’s partnering with developer Civico on 43 affordable housing units at 1165 Washington St., a project just starting its zoning approvals process.

“We’ve been lucky in the towns where we’ve worked to have really strong planning staff,” Madden said. “I can’t see how anything would get done without them, frankly.”

For-profit commercial and multifamily developers also take the city hall planning apparatus into account when evaluating potential sites. Communities with fractured lines of authority to approve projects are a red flag, said Brian Iammartino, co-founder and managing partner of Boston-based developer btcRE.

In most communities, btcRE favors projects that don’t require special permits or zoning approvals, such as building conversions involving a change of use. The result is savings in time and money that would be spent on consultants during permitting, Iammartino said.

Such business imperatives come at the expense of projects such as multifamily housing that require a more lengthy approval process, he noted.

“Not having the [municipal] staff to help permitting move along is a part of that, from the perspective of a developer,” he said. “What I do as a developer, whether it’s in Somerville or Waltham or Watertown, is to get things done as quickly as possible.”

Housing developers say a town’s lack of professional planning staff can mean spending significant time and money on development proposals before finding out that they are politically impossible.

Waltham Doesn’t Have a Plan

In Waltham, a perceived shortage of sufficient professional planning staff has been a political football in recent years.

The city of 65,000 was one of the first to benefit from the construction of Route 128 in the 1950s and the expansion of its tax base at new office parks that offered an alternative to Boston’s then-declining fortunes. Today, Waltham has nearly 13 million square feet of office and lab space, according to brokerage Newmark, representing the largest inventory of any community on Route 128 and more than double that of the second-biggest suburban commercial real estate submarket in Burlington.

But unlike many suburbs, Waltham doesn’t have a planning board, and developments are reviewed by the City Council and Zoning Board of Appeals. The full-time Planning Department staff at city hall has a $1 million budget, of which $346,000 goes to personnel, according to the fiscal year 2023 budget. But the department does not review development applications, focusing instead on the federal Community Development Block Grant program.

“What has worked best for us in Waltham is building relationships with the building inspector, the Fire Department and those kind of groups that we can pick up the phone and talk to directly,” Iammartino said.

In an unsuccessful challenge to incumbent Jeannette McCarthy in 2019, former City Councilor Diane LeBlanc argued that a “complete lack of planning has crippled our infrastructure.” LeBlanc cited the city’s failure to update its master plan for decades, and new development overwhelming transportation networks.

Malden Eliminates Silos, Gets Results

Malden, a similarly-sized city with growth pressures fanning out from Boston, recently upgraded land-use departments and replaced decades-old ways of doing business with developers.

Until 2021, the city of Malden didn’t have a full-time planning department, despite a recent building boom that brought more than 1,000 new market-rate apartments to its downtown in the previous decade. The city’s primary land-use agency was the Malden Redevelopment Authority, a relic of the urban renewal era created in 1958, which had limited powers and long-range planning responsibilities.

In 2021, as Malden started to attract interest from life science developers, Malden Mayor Gary Christenson agreed to support the creation of a new Office of Strategic Planning and Community Development headed by Deborah Burke, the former Malden Redevelopment Authority director. The department includes a city planner, Michelle Romero, who advises the Malden Planning Board, a transportation planner, and grant writer pursuing state and federal funding and a transportation planner.

“We’re working more jointly and collaboratively instead of in silos on various projects,” Burke said.

As an example, the department put together a checklist for a developer building one of the first housing projects under the city’s new inclusionary development policy. The ordinance requires at least 15 percent affordable units in projects with eight or more units.

Steve Adams

It’s the sort of guidance that smaller development firms need to navigate the permitting process, Burke said.

“It’s a simple and easy to understand checklist for somebody who isn’t one of the large-scale developers, to walk their way through it,” Burke said.

Sarah Barnat, a former director of Urban Land Institute Boston-New England, said talented full-time planning staff are in high demand in Greater Boston and turnover is high.

“So many towns rely on volunteers, but a lot of this work ends up being a full-time job, and to have some longevity within those positions is helpful,” said Barnat, who completed the Holmes apartment project next to the MBTA’s Beverly commuter rail station in 2019. “The really good planners are being recruited from city to city.”